Viruses 101

What do rabies, cold sores, and COVID-19 all have in common? They are each caused by a viral infection.

Viruses have co-existed with humans from our earliest evolutionary origins—and well before that. To date, scientists have identified at least 219 virus species that are able to cause disease in humans, and a few more are discovered each year.1

That number likely just scratches the surface of the number of viruses that inhabit our world. According to recent estimates, a minimum of 320,000 viruses exist within the mammalian class of animals alone.2 Even more virus species infect birds, reptiles, and plants. According to some estimates, there are 10 million times more viruses on earth than there are stars in the universe.3

What is a Virus?

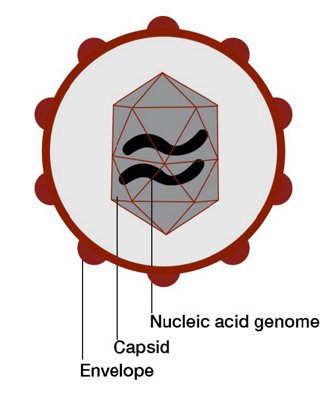

Viruses are tiny particles—much smaller than bacteria, which are microscopic single-celled organisms. A single virus is called a virion, and it’s comprised of RNA or DNA genome enclosed in a protein covering called a capsid. Some viruses are also enclosed in an outer lipid membrane, called an envelope. Viruses cannot reproduce by themselves. Instead, they hijack a host cell and force it to begin replicating the virus.

It took scientists over two centuries after discovering bacteria to identify and confirm the existence of viruses because they were too small to be seen with early microscopes. In the 1890s, scientists realized there were disease-causing agents that were non-filterable—meaning they flowed through filters designed to capture bacteria. Because they passed through these filters, some scientists thought viruses were a kind of liquid poison. But over the years, new imaging techniques, particularly the electron microscope, have enabled us to see these tiny virus particles.

How Does a Virus Operate?

Viruses are non-living particles that commandeer living cells to force them to create new copies of the virus. When a virus encounters a viable host cell, it attaches to the cell and can enter by fusing to the cell’s outer membrane or being engulfed into the cell’s endosome (depending on the type of virus). Either way, once fusion occurs, the virus releases its DNA or RNA. Then it compels the host cell to use its own replicative processes to begin creating copies of the virus’s genetic material and viral protein. These elements then assemble into new virions that are released from the cell to seek new cell hosts to invade.

This viral takeover is remarkably effective. In fact, each infected host cell is turned into an efficient factory that, depending on the virus, can manufacture up to a million new virions.4 Each cell infected with an influenza virus produces up to 10,000 new virions—but in total, an infected person can have up to 100 trillion flu viruses in their body after just a few days.3

Viruses are generally quite specific as to which cells they can infect and the type of host. The viral proteins located in the capsid must fit with receptor molecules in the target host cell—much like a key fitting into a lock. That’s why some human viruses can only attack cells within respiratory airways, while other viruses attack the liver, the lining of the brain, or blood cells. The specific lock and key binding needed for a virus to gain entry into a cell is also why it’s difficult for viruses to jump from one host reservoir to another (for example, to move from bats to humans).

How is a Viral Infection Diagnosed and Treated?

Viral infections can cause distinctive symptoms, like the telltale cough and congestion of a cold, or the headache and stiff neck due to viral meningitis. But it is difficult to diagnose a viral infection based on symptoms alone. That’s because many pathogens can cause similar, overlapping symptoms. That cough, for instance—is it due to COVID-19 or influenza? Or something else?

Laboratory testing is the only way to know with confidence which virus is causing troubling symptoms. Many diagnostic tests have been developed to detect the presence of viruses, viral antigens, or specific antibodies the body creates as it fights off a viral infection.

Testing for one virus at a time can be a slow, laborious process. Once one suspected virus is ruled out, the next likely virus must be tested. On the other hand, syndromic testing from BIOFIRE enables labs to test for multiple viruses, and other potential pathogens, all in one, rapid test. The BIOFIRE® FILMARRAY® Panels offer fast and accurate answers on a broad menu of potential pathogens, taking the guesswork out of infectious disease diagnostics.

For example, BIOFIRE’s COVID-19 solutions target several viruses and bacteria that can cause respiratory illnesses, including SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), influenza viruses, several cold-causing viruses, and the bacteria responsible for whooping cough, among others.

Rapid answers on a broad menu of possible pathogens may enable physicians to put patients on appropriate therapy sooner. In the case of viral infections, that may mean simply treating symptoms (like fever) while the patient’s immune system works to fight the virus. Antibiotics are ineffective for treating viruses, and antiviral medications have only been developed to treat a few specific viruses.

Roughly 120 years after scientists first became aware of the presence of viruses, we are still learning about these miniscule particles. The next few decades will undoubtedly bring crucial advancements in our understanding of viruses and how to combat them.

Learn More:

References:

- Woolhouse M, et al. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2012) 367: 2864–2871.

- Columbia Public Health, Center for Infection and Immunity. Accessed on Jan 8, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/center-infection-and-immunity/first-estimate-total-viruses-mammals

- Zimmer C. (2013, Feb 20). An infinity of viruses. National Geographic. Accessed on Jan 8, 2021. Retrieved from http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2013/02/20/an-infinity-of-viruses/

- Cohen F. Biophysical Journal. (2016) 110:1028–1032.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE:

- Diagnostic Digest